The Internet of Things (IoT) refers to any network of physical objects that embeds technology to communicate and sense or interact with external environments and their own internal states. The devices that are used in these kinds of networks are mostly wireless sensors, control systems, and technologies for home and building automation, all of which require smart, efficient, and cheap forms of power.

Scientists from the U.S. Department of Commerce’s National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have tested the ability of three different solar module technologies to power Internet-of-Things devices such as wireless temperature sensors.

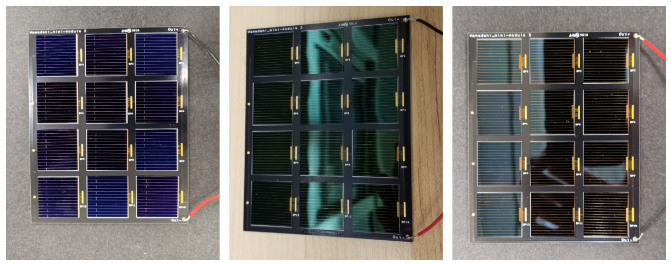

The group tested, in particular, three mini-modules made with 12 individual 2 cm × 2 cm solar cells relying on silicon, gallium indium phosphide (GaInP), and gallium arsenide (GaAs), respectively, that were custom-built for low light energy harvesting. The three devices have a power conversion efficiency of 9.3%, 23.1% and 14.1%, respectively.

The panels were used to charge low-capacity batteries powering the sensors. “For all three cell technologies, three cells were wired in series and four columns of such cells were connected in parallel to provide the voltage required to satisfy the charging circuit’s minimum voltage requirement,” it stated. “The substrate that holds the cells is a printed circuit board (PCB) with a pair of gold-coated copper contacts for each cell.”

The modules were placed underneath a warm white light-emitting diode (LED), housed inside an opaque black box to block out external light sources, which generated light at a fixed intensity of 1,000 lux, comparable to light levels in a well-lit room. The rechargeable lithium-ion batteries have a maximum charge voltage of 4.2 V, a nominal charge capacity of 40 mAh and are designed for 3.6 V operation. “The circuit is designed with a capacitor to supply the burst current at the output pin to charge the battery,” the U.S. group said.

The measurements showed that the GaInP panel was able to supply the most power to the circuit, at 3.05 mW, while the GaAs and silicon panel provided 1.34 mW and 1.36 mW, respectively. The GaInP module was also able to charge the battery in the least amount of time, followed by the GaAs and silicon modules.

Despite its poor performance, the research group decided to conduct a second experiment on the silicon panel, given its lower costs compared to the other two technologies, and sought to understand if these devices may be suitable for low-demand IoT devices. The mini-module was linked to a wireless temperature sensor with lower power requirements and placed under the same illumination conditions as the previous experiment. When the sensor was turned on, powered by the PV panel, it became able to feed temperature readings wirelessly to a computer nearby.

After two hours, the light in the black box was switched off and the sensor continued to run. The battery, meanwhile, depleted at half the rate it took to be charged. “Even with a less efficient mini-module, we found that we could still supply more power than the wireless sensor consumed,” said NIST researcher, Andrew Shore. “We’re turning on our lights all the time and as we move more toward computerized commercial buildings and homes, PV could be a way to harvest some of the wasted light energy and improve our energy efficiency.”

The findings of the experiment can be found in the paper Indoor light energy harvesting for battery-powered sensors using small photovoltaic modules, published in Energy Science & Engineering.