Offshore floating solar panels are an ideal way to address the solar energy needs of high population density countries like Indonesia and Nigeria., according to a study published July 27, 2023 by David Firnando Silalahi and Andrew Blakers, both of the School of Engineering at the Australian National University. Furthermore, global heat maps show that the Indonesian archipelago and the Gulf of Guinea near Nigeria have the greatest potential for floating solar arrays.

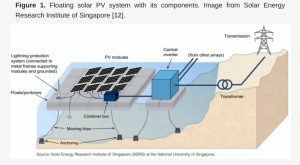

Floating solar, also known as floating photovoltaic (FPV) or floating solar farms, involves the installation of solar panels on water bodies such as lakes, reservoirs, and canals. Experiments with floating solar date back to the 1970s. However, recent advancements in technology and growing environmental concerns have sparked renewed interest in installing floating solar systems on the surface of the oceans.

While land-based solar options may be limited in highly populated regions due to land use conflicts, offshore floating solar offers an attractive alternative, especially in regions that experience calm seas with minimal waves and winds. Such areas could generate up to one million TWh per year, five times more than the solar energy needs of a fully decarbonized global economy supporting 10 billion affluent people, the researchers conclude.

These proposed offshore solar installations would be located in the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone, known to offshore sailors as the doldrums for their lack of wind and calm seas. In the days of sail power, ships would often get stuck there with no wind to fill their sails, sometimes for weeks.

The ICTZ extends approximately five degrees north and south of the equator, in which the prevailing trade winds of the northern hemisphere collide with the trade winds of the southern hemisphere, cancelling each other out. Due to intense solar heating near the equator, the warm, moist air is forced up into the atmosphere like a hot air balloon. Because the air circulates in an upward direction, there is often little surface wind in the doldrums. Below is an excerpt from the study.

“This study assesses the potential of ocean surfaces for floating solar PV sites. Preferable places for maritime solar panels are those where maximum wave heights and wind speeds are low because this reduces the cost of the engineering defenses required to protect the panels. 40 years of maximum hourly wind speed and wave height data were analysed to map the preferable sites for floating solar PV. The largest wave heights and wind speeds experienced during the years 1980 to 2020 were selected to characterize suitability, since it is maximum values that drive the cost of engineering defenses.

“The ocean’s surface covers 363 million km2, which is about 72% of the earth’s surface. The scope of this research encompasses sea and ocean surfaces within 300 km of land. The analysis is conducted at a spatial resolution of 11 km to provide an assessment of the potential for maritime floating solar PV sites. It is the first comprehensive survey of the scope required for maritime floating solar PV that considers factors such as hourly maximum wave height and hourly maximum wind speed.”

Calm Seas & Shallow Waters

Most of the global seascape experiences waves larger than 10 meters (65 feet) high and winds stronger than 20 meters per second (70 km/h)。 Several companies are working to develop engineering defenses so offshore floating panels can tolerate those conditions. However, benign maritime environments along the equator require much less robust and expensive defense mechanisms. Regions that don’t experience waves larger than 6 meters or winds stronger than 15 meters per second could generate up to one million TWh per year the study found.

Shallow seas found close to large land masses are preferred for anchoring the floating solar panels to the seabed, according to a report on the research by The Conversation. However, because of the proximity to land, careful attention must be paid to minimizing damage to the marine environment, fishing activities, and shipping lanes. The researchers also note that global heating may alter wind and wave patterns in ways that are not easily predictable.

Floating solar installations on the surface of the ocean present challenges, particularly from salt corrosion and marine fouling. Yet despite these challenges, they believe offshore floating panels will provide a large component of the energy mix for countries that have access to calm equatorial seas. They predict that by mid-century, about a billion people in these countries will rely mostly on solar energy.

“We have found the most suitable regions cluster within 5–12 degrees of latitude of the Equator, principally in and around the Indonesian archipelago and in the Gulf of Guinea near Nigeria. These regions have low potential for wind generation, high population density, rapid growth (in both population and energy consumption) and substantial intact ecosystems that should not be cleared for solar farms. Tropical storms rarely impact equatorial regions,” the researchers say.

Indonesia & West Africa

Indonesia is a densely populated country, particularly on the islands of Java, Bali, and Sumatra. By 2050, its population may exceed 315 million people. About 25,000 square km of solar panels would be required to support an affluent Indonesia after full decarbonization of the economy using solar power.

Indonesia has the option of floating vast numbers of solar panels on its calm inland seas. The region has about 140,000 square km of seascape that has not experienced waves larger than 4 meters or winds stronger than 10 meters per second in the past 40 years. Indonesia’s maritime area of 6.4 million square km is 200 times larger than required if Indonesia’s entire future energy needs were met from offshore floating solar panels.

The waters in the Gulf of Guinea near West Africa also would be suitable for offshore floating solar installations, which would bring abundant renewable energy to large parts of that continent.

The Takeaway

Enough sunlight falls on the Earth every 90 minutes to meet the energy needs of all 8 billion people currently living on our little blue lifeboat at the far edge of a minor galaxy for a year. All we need to do is harvest it in order to eliminate all carbon and methane emissions from the energy sector. As the world transitions to electric vehicles, that sector will be decarbonized as well.

This research suggests floating solar on the surface of the oceans could meet the combined energy needs of the entire world five times over. Will it be easy? No it will not be, just as it is not easy to extract oil from the North Slope of Alaska, build pipelines or large tankers, enormous refineries, and complex systems to deliver oil, gasoline, methane gas, and other industrial products to the end users.

We face extinction. Perhaps it is time to stop whining about how hard it will be to transition to renewable energy and start building the systems that will allow us to thrive in the future. Instead of building new coal and methane and nuclear powered generating stations, it is time to stop digging the hole deeper and start thinking about how to survive for millennia to come. This research is a road map to a sustainable future. We should follow it.