Hydrogen – the universe’s smallest molecule today holds perhaps its loftiest promise. However, the energy transition needs to be thoughtfully designed. Nicky Ison, WWF Australia’s energy transition manager, tells pv magazine Australia about four things that need attention to safeguard the emerging hydrogen economy and ensure it begins clean.

1. Stop using colors

“There’s fossil fuel hydrogen and renewable hydrogen, and that’s the least confusing way of describing it,” Ison says, plainly.

Currently, the vocabulary around hydrogen’s origin is explained by a rainbow of colours, from green to blue to gray to brown. It’s confusing for people in the industry, let alone laypeople. In fact, former Australian Prime Minister Malcom Turnbull also brought up the issue of hydrogen’s many colors at the Smart Energy Conference earlier this month, saying that “green hydrogen is the only type of hydrogen we should be planning for.”

Turnbull flatly called “BS” 0n “blue hydrogen,” or hydrogen produced with fossil fuels where emissions are supposedly offset by carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology. “There is no other color [other than green] of hydrogen that you can responsibly support,” he said.

The Smart Energy Council is working on this specific issue. It introduced a Zero Carbon Certification Scheme to guarantee that hydrogen and all its subsidiary materials are made completely from renewable energy.

2. Public money for renewable hydrogen

The reason, Ison says, is that hydrogen produced using fossil fuels simply doesn’t hold any promise for a cost curve reduction, since it is a mature industry. Renewable hydrogen, on the other hand, will inevitably drop in price significantly through economies of scale.

While renewable hydrogen is still significantly more expensive to produce today, Ison points back to 2009, when there was a huge cost difference between solar electricity and traditional electricity. Government backing of solar quickly closed that gap, getting Australia to where it is today. Like wind and solar, the electroyzers used to make renewable hydrogen are a modular technology, which means they will follow a similar trajectory down in terms of cost, especially with government backing.

The other reason that public money should be more shrewdly spent is, of course, to reach climate targets.

“We should not be investing in technologies that are not zero emissions,” Ison tells pv magazine Australia.

3. Decarbonize the hydrogen industry

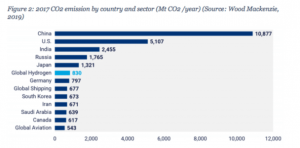

Global hydrogen accounts for 1% of greenhouse gas emissions, so decarbonizing the existing industry should be top priority, Ison says.

Around 98% of the hydrogen produced today uses fossil fuels in its production. This accounts for more CO2 emissions per year than the global aviation industry and global shipping, according to Wood Mackenzie. This, Ison says, makes it clear that hydrogen’s greening process needs to begin at home in the existing hydrogen industry.

4. Focus on industrial processes

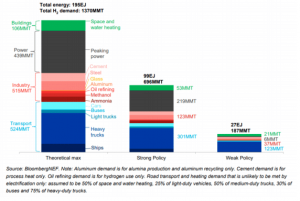

Renowned journal Nature caused a stir when it published a piece from a German-Swiss research team concluding that the use of hydrogen-based fuels should be prioritized in sectors that are difficult to electrify, such as long-distance aviation, feedstocks in chemical production, steel production and high-temperature industrial processes.

“Hydrogen as a universal climate solution might be a bit of false promise,” it said.

Ison largely agrees. She says the focus should be on integrating hydrogen where it’s needed most, not in areas where electrification is already established and working well, such as electric vehicles.

“Renewable hydrogen is absolutely essential for decarbonisation, but we shouldn’t waste it on processes where we could use renewable electricity directly,” Ison said.

If we focus on industrial applications, Australia will be able to export hydrogen, probably in the form of ammonia, Ison says. “But the biggest opportunity is actually is on-shoring industrial processes.”

Role reversal

Our incumbent system is based on the characteristics of fossil fuels – which are expensive produce, but exceedingly cheap and easy to transport. Renewable energy, on the other hand, is cheap to produce, but costly and difficult to transport.

If the ease of fossil fuel transportation meant manufacturing and industry could be pushed offshore where labor is cheaper, this model loses its legs as the world decarbonizes. This shifts the foundational nature of the industrial sector globally.

Like the authors of the Grattan Institute’s ‘Start with steel’ paper, Ison says this shifts holds a lot of potential for Australia. By bringing industrial processes like steelmaking and ammonia production back onshore, Australia could drive a manufacturing boom, she says.