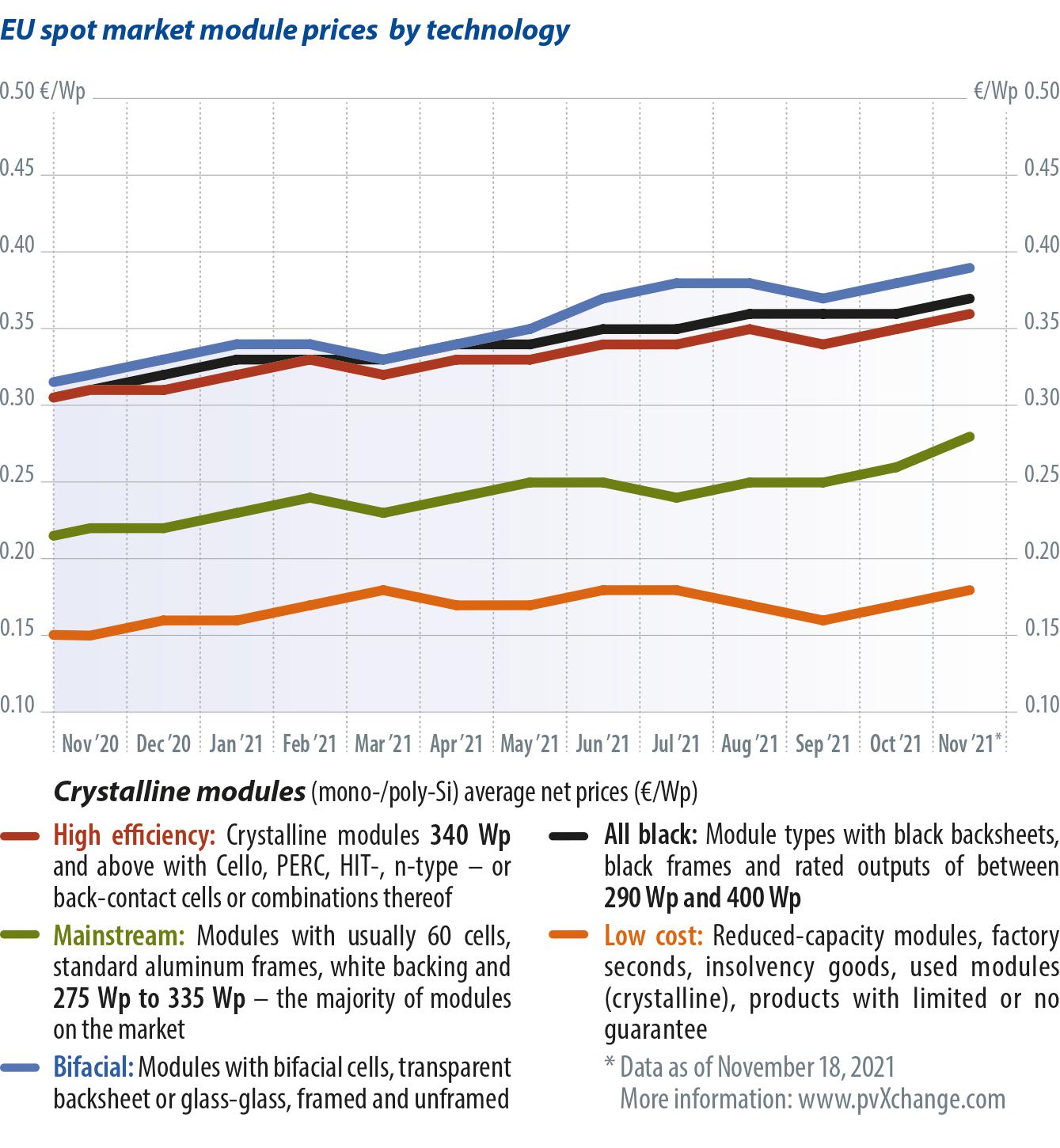

Even the few lower-capacity PV products still available in the market in 2021 – that is, below 300 W for 60/120 cells or 400 W for 72/144 cells – are now being traded at rates that are only acceptable in the most dire of circumstances. Given high historical feed-in tariffs, such terms are only tolerable for replacement of defective modules in existing plants. In new plants, panels with such low efficiencies – referred to here as mainstream modules – are scarcely viable.

If we look at the value of the feed-in tariff in December 2018 in Germany, for instance, and how much or how little will still be granted to producers of PV power in December 2021, the whole quandary becomes apparent. Whereas we could still expect feed-in tariffs of €0.08/kWh to €0.12/kWh for PV systems connected to the grid in late 2018, in the coming months we will have to settle for just €0.047/kWh to €0.073/kWh, depending on the size of the system and whether the market premium model is applied. And this declining remuneration has unfolded against the backdrop of unchanging module prices in terms of euros per watt-peak. After all, module efficiency has increased by an average of 20% (relative) and individual module output by as much as 25%, due to the enlargement of cells and modules. Thus, thanks to the reduced number of modules per kilowatt of installed power, installation expenses have been reduced, which has in turn helped to bring down overall costs. Nevertheless, it is becoming increasingly difficult and unattractive to plan and operate plants without a high proportion of self-consumption.

In Germany, the number of new installations has continued to be comparatively high in recent months, which has led to feed-in tariffs falling at a degression rate of 1.4% per month. This is due to the target corridor of 2.5 GW per year, which will be greatly exceeded in 2021 with an estimated 4.5 GW to 5 GW, triggering the sharp reduction in feed-in tariffs. In view of the need to add more than 10 GW per year, this target is an outdated symbol of the outgoing German government’s unimaginative energy policy. As there is a general consensus that the expansion of PV is an essential pillar of future climate protection, however, there is justified hope that the incoming federal government will very quickly introduce corrective measures to make new installations more attractive again. At the moment, the only sector that is booming is the small-scale PV sector, where module prices do not play such a decisive role.

What’s in store for 2022

It is difficult to make predictions today about the future climate policy of the new “traffic light” coalition in Germany and the governments of other countries so soon after the somewhat underwhelming outcome of the COP26 international climate conference in Glasgow. In principle, we can certainly expect a very positive environment for the renewable energy sector. Ultimately, we have no choice but to step on the (bio)gas in advancing renewables. As always, however, the devil is in the detail, and it is no secret that the clumsy environmental and industrial policies of the past have done considerable damage. It will take some time for this changed constellation to have an impact on market development and for new, attractive opportunities to arise for players in the renewables space. In the meantime, the laws of supply and demand are at work, and some turbulence can certainly still be expected as a result.

The available supply of modules and many other solar components cannot meet the current demand, a dynamic that is driving up prices. The reasons for this are varied, and I have already discussed them several times in recent months. In addition to supply chain disruption and high transport costs that have made some shipments obsolete, China’s energy problems are now also coming into play. In fact, some manufacturers have already had to cut their capacity utilizations by 10 to 20%, resulting in fewer precursor materials that are urgently needed for module production. This has also brought the supply of fresh modules for the global market to a standstill. Furthermore, it has reduced the flow of goods to Europe, which means that delivery dates are often significantly delayed. The market explosion in China predicted months ago has so far failed to materialize. For the coming year, gigantic additions of up to 100 GW have already been announced.

However, since such forecasts have rarely come true up to now, we should probably not be too concerned about module availability in 2022. According to the sales staff of individual manufacturers, module prices are also not expected to make any more big upward leaps, but will soon stabilize at the current high level. However, producers do not necessarily want to tie themselves to specific prices.

A popular strategy at the moment is to quote free on board prices in U.S. dollars – that is, prices ex-works in Asia that explicitly exclude the risks of volatile transport prices and exchange rates. Vague sliding-price clauses have also entered the discussion, again with a view to minimizing risk.

However, buyers should negotiate the base price well before agreeing to such conditions. It may also be a good strategy to wait until the end of the quarter. Experience has shown that many manufacturers clear out their warehouses around mid-December, so there may still be a bargain or two to be had.