After a two year hiatus, PV Tech’s flagship module event, PV ModuleTech – encompassing module quality, supply chains, reliability testing and factory auditing – will return live in June 2022, and will be hosted for the first time in the US.

This article outlines the issues specific to PV module supply to the US today and the themes that will dominate the PV ModuleTech 2022 event, to be hosted at PVEL’s new site in Napa, California, on 14 – 15 June 2022.

The discussion below also explains why PV module supply to the US market today is more scrutinised than anywhere else in the world, seeking to answer the question: why has module selection for US projects become risky and complicated now?

What makes module supply to the US different to other regions globally

For years, due diligence towards shortlisting and selecting modules for the US market has been more detailed and exhaustive, compared to buying modules in any other part of the world. At the same time, the US market remains the one to ‘crack’ for almost all leading PV module suppliers today. These two factors serve to create an incredibly difficult supplier landscape for module buyers in the US today.

Let’s look quickly at how the world has become segmented when choosing module suppliers.

China – the largest end-market by a country mile today and consuming about a third of all modules produced globally – has no specific import duties in place. However, unofficially, it is a market only for domestic players. Virtually no modules get imported into China; it is a one-way street. Module supply deals are routinely awarded from one state-owned entity to another, or at arms-length to subsidiary and affiliated companies that do the manufacturing.

But to understand the bigger picture, it is useful to look at some of the numbers in terms of module production in China today: how much of this is ‘self-consumed’ (manufactured and deployed locally); how much product leaves the country; where do these modules ship to?

During 2022, about 210GW of modules will be produced in China. About 30-40% will stay in the country, and the remainder (60-70%) will be exported around the world, with the exception of the US and (interestingly) Taiwan. India, having imported high volumes from China until now, is expected to reduce its dependency on Chinese modules this year, but of course the country will still need cells to be imported for some time yet.

Southeast Asia (specifically Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia and Cambodia) will see about 25-30GW of modules produced in 2022. Approximately 75-80% of these modules will be shipped to the US market. The remainder will end up in new solar farms in the region (Southeast Asia), or get turned into OEM product and sold somewhere else by a different company.

By comparison, the rest of the world is rather straightforward. Most of the modules produced in countries such as Taiwan, South Korea, India, Europe and the US stay in these locations. South Korea and India have export volumes of note, in particular the uptick in 2021/2022 Indian exports to the US market (filling the gap created by Chinese companies choosing to fuel the domestic China market now). A similar dynamic has also seen European exports to the US grow recently.

Product made in the US stays in the US. But while there are other import restrictions in place (based upon origin of manufacturing), the 2012 AD/CVD and recent Section 201 rulings have meant that the US is the only major end market for now that needs to have product made outside China.

Hence the reason for the massive shipment volumes coming from Southeast Asia (putting aside First Solar’s thin-film fabs in Malaysia and Vietnam that are excluded from the silicon-based duties).

The US market also has a layer of scrutiny not seen anywhere else in the world, specifically pertaining to reliability testing, and the involvement of US-specific IEs and technical due-diligence stakeholders working within or for financial institutions investing in new solar infrastructure.

On top of this, the US is the one country that has been at the forefront of imposing the need to check whether any of the product (specifically polysilicon or mg-Si) comes from Xinjiang.

All put together, buying a PV module in the US today is more intensely scrutinised than anywhere else in the world, and by quite some margin. And the US has to import about 70-80% of the modules it needs each year.

How the US needs more domestic manufacturing, and not simply assembling imported cells into packaged modules (as has been the trend for the past few years). It is one of the rare cases where the US and India are in some kind of alignment today.

And just to make matters worse, in the past 12 months, product availability from the leading players has been in short supply, mainly due to these companies being able to command higher margins by shipping product to projects within China (and avoiding increased shipping costs, while distancing themselves from the Xinjiang issue in the meantime).

The net result of this in 2022 is that the US market is by far the highest ASP country for utility-scale solar modules (DDP terms), and with a range of suppliers having to be considered for 2022 deployment that have minimal track-record until now in the country.

In fact, it is astonishing today looking at the gulf between module selection in the US and the rest of the world. Even across Europe, it seems that many module buyers are living largely in the past, fixated on factors that defined the PV industry 5-10 years ago, and only now waking up to availability and pricing shocks. Wider afield, many people just want the cheapest product tomorrow.

How on earth did this situation arise? Why are module buyers globally not looking at PV module supply to the same level as the US downstream segment? Is module selection in the US just 3-5 years ahead of the rest of the world (bar China)?

So, if there was a year that PV ModuleTech should be held in the US, it is 2022, and as soon as possible!

Supply of PV modules to the US market in 2022 and beyond

Until recently, module supply to the US was rather prescriptive. First Solar held a market-leading position, focused on utility-scale projects (in-house developed in the past, or third-party supplied), with thin-film panels made in Malaysia, Vietnam and Ohio that have been (and likely always will be) absent of any incremental tariffs as seen for silicon-based modules.

The next category of module suppliers to the US have been the leading c-Si global players, headquartered in China and with varying degrees of cell/module capacity and OEM agreements across production sites in Southeast Asia (mostly Malaysia, Thailand and Vietnam). This grouping is dominated by JinkoSolar, LONGi Solar, Trina Solar, JA Solar and Canadian Solar. Each of these companies (with the exception of LONGi) has been listed in the US previously (NASDAQ or NYSE).

JA Solar and Trina Solar delisted several years ago, in preference of China listings that were more conducive to company valuation and capital to fund capacity expansion. JinkoSolar and Canadian Solar are currently in the process of doing this change. Jinko’s move is very similar to what JA Solar and Trina did before. Canadian is carving out its manufacturing business (dominated by PV module sales) for a China listing (under ‘CSI Solar’), not a million miles removed from what ReneSola did many years ago, whereby the US-listed part focuses on downstream project development, site build out, and (typically) post-build flipping.

By the end of 2023 however, each of Jinko, Trina, LONGi, JA and Canadian (renamed CSI Solar) will be a Chinese-listed PV module manufacturing entity; still serving the US market from Southeast Asia cell/module production (in-house and/or OEM-based). Jinko is the only company here that has set up US-based manufacturing (modules only).

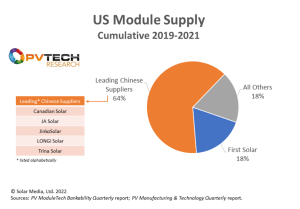

The graphic below looks at the total PV module supply to the US market in the three-year period covering 2019 to 2021. I have split out the two categories above: First Solar and the leading Chinese suppliers (the five companies listed above).

During the three year period 2019 to 2021, First Solar and the five leading Chinese module suppliers accounted for 82% of all module shipments to the US market. During 2022 and 2023, many of the companies contributing to the All Others segment will go through a period of increased shipments.

During the three year period 2019 to 2021, First Solar and the five leading Chinese module suppliers accounted for 82% of all module shipments to the US market. During 2022 and 2023, many of the companies contributing to the All Others segment will go through a period of increased shipments.

The ‘All Others’ category includes a wide range of module suppliers, business models and is heavily weighted to residential and small-scale rooftop/ground installations. This grouping includes companies like Maxeon (former SunPower manufacturing operations) that is still evolving its strategy and raison d’être globally (and US specific); and at least for now, LG Electronics. REC Group (now owned by Indian conglomerate Reliance) and Q CELLS (now operating within Korean Hanwha Solutions) also feature prominently in the ‘All Others’ segment, with recent sales and marketing efforts in the US directed towards rooftop installations.

While one might assume that most of the current module supply arrangements would involve either First Solar or one of the five leading Chinese companies listed above, this is not the case. All of these companies are basically ‘sold out’ for any meaningful new shipment volumes to the US in 2022. In the case of First Solar, this is coming purely from capacity constraints. For the others, it is their choice, in that they are choosing to limit additional commitments to the US this year (for the reasons I cited above). Europe is seeing a similar dynamic, in terms of modules available for local sales teams during 2022. It is worth emphasising again; it is a (module) seller’s market.

Therefore, all the focus today in the US is on the ‘All Others’ category above; both from the circa. 20-30 module suppliers that have made up the rest of the US market in the past three years, or the 10-20 new ‘names’ that are chomping at the bit to win business in the US with ASPs they can’t quite believe are on offer. Furthermore, most (if not all) legacy US module assembly companies (historically with nameplate capacities well below the gigawatt-level), that had previously carved out a regional niche for residential and small-scale industrial/commercial shipments, are now seeing the utility-scale segment as a new growth opportunity.

The door has also been opened for some Indian PV module producers, never shy of seeking overseas opportunities when they arise, as seen in the European market briefly when MIP was in place, and European-based module production sites (higher margins can be obtained today by shipping to the US, than selling domestically in Europe).

Even if you subscribe to the notion that the current modus operandi of buying PV modules in the US (Southeast Asia assembly by Chinese companies, short-term opportunities for Indian module assembly companies) is a passing phase – and eventually this somewhat trying period will come to an end – it doesn’t actually help anyone looking to buy modules for shipments in 2022 and 2023. It could be 2024 before things change meaningfully; US manufacturing, greater Chinese investment in wafer and cell capacity in the US, for example.

Therefore, like it or not, there is probably a two-year window where understanding PV module supply to the US will need considerable scrutiny, understanding and questioning. Right now, module supply – similar to different phases in Europe over the past 20 years – is seeing a host of companies selling within the US, but simply buying modules made by other companies in Southeast Asia. They are in reality distributors, not module suppliers. Most trade on a brand name either currently making panels in China for non-US supply, or from a time when the company was a module producer before moving to a reselling model. Europe has a dozen or so companies doing this today; the US market might have about twice this number. It only adds to the confusion. Buying through resellers or OEM suppliers doubles your risk in terms of companies going bankrupt or insolvent, or defaulting on contractual agreements.

How to get involved at PV ModuleTech, Napa, California, 14-15 June

The PV ModuleTech 2022 agenda is focused purely on the key issues that are important to investors, developers and EPCs buying modules for 2023 to 2025 delivery within the US.

Who will be the main suppliers then? Which module technologies will they be selling? Where is this product going to be made and can the supply-chain be audited? How reliable are the modules? How will they perform in extreme conditions? What will be the US market pricing in 2023 and 2024? How are import tariffs and duties likely to evolve?

Are the existing PV module suppliers in good financial health? Which ones are at risk? Which of today’s module suppliers from overseas will likely retreat back to their domestic market after 2022? Will new cell and module capacity in the US make any difference in 2022 or 2023? What will PV production in the US look like moving into 2025?

In addition to the two days of presentations, I am sure many will be keen to visit PVEL’s new facility in Napa, and some might just be happy to be in Napa Valley in June for the wine. The numbers on-site will be limited, and there is only a small number of tickets available for purchase (on a first-come, first-served basis). Places are limited also to a maximum of two people per company. Full details on how to attend can be found at the link here.

For those in need of more immediate assistance in understanding module supplier options to the US (or indeed globally), consider subscribing to the PV ModuleTech Bankability Ratings Quarterly report. More details can be found at the link here.