Finlay Colville, head of market research at Solar Media, ranks the top 50 module suppliers in the PV industry today, using the proprietary methodology developed at PV Tech, on the back of analysing several hundred companies supplying PV modules over the past 15 years.

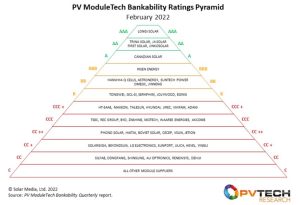

For the first time, the top 50 are ranked and categorised into eleven discrete ratings bands, from AAA to CC. Also, within each of the bands, each company is listed by most bankable to least bankable.

Three years on from the first release of the PV ModuleTech Bankability Ratings, I reflect in this article on what makes a PV module supplier bankable, and what the most common red flags are when undertaking due diligence on supplier selection for large-scale utility-based solar projects.

Methodology and validation applied when benchmarking module suppliers

During 2019, I explained how the PV Tech market research team went about benchmarking the 100-plus module suppliers that accounted for >98% of all module shipments globally. This included six feature articles: the first appeared on PV Tech in July 2019, here. The final one, here, was published in August 2019.

Before we released the bankability ratings analysis, we considered it essential to explain the underlying methodology and the accuracy of the validation processes. For a decade prior to this, it was clear that the PV industry was lacking any credible means of benchmarking module suppliers.

Benchmarking is everything: understanding the relative strengths and weaknesses of companies, at any given time, regardless of the industry’s condition. For example, when there is a downturn in the sector – oversupply, valuation of the renewables sector, trade issues, technology change – individual company assessment can only be done in relation to other companies’ performance. Conversely, when there is an upturn, everyone tends to benefit, typically accompanied by an increase in module shipments, profitability and entity valuation.

Understanding the importance of benchmarking at any given time is key. But the underlying methodology has to be forward-looking. This brings us to the second key issue – validation. Once a set of input conditions is established, alongside an analytical methodology framework, it should be possible to go back in time and see which metrics (manufacturing or financial) ultimately led to an upturn or downturn in fortunes as they relate specifically to PV module supply activities. This allows us to assess risk better in today’s market; or to be more specific, what are the ‘red flags’ to keep under review for each module supplier (or parent entity, where the PV module business is not the main contributor to revenues). I will return to this later in the article.

The Bankability Pyramid at the start of 2022

Our definition of ‘bankability’, as outlined in the articles back in 2019, remains the most comprehensive one in the PV sector today. For sure, other rankings lists exist for PV module suppliers, but they tend to be over-simplified or lacking knowledge of the sector itself or the individual company’s standing in the market. I will touch first on why these can in fact be misleading, before revealing the latest bankability pyramid hierarchy at the start of 2022.

Top 10 module supplier rankings (based purely on module shipments) are useful to some extent, as you can see which companies are shipping the greatest volumes annually, and how suppliers’ rankings go up and down over the years. People like to read these top 10 charts; marketing departments tend to like them if they show their company favourably compared to their peers. But they say nothing about geographic shipment splits (e.g. were more than half the modules made in China and stayed in China?); they don’t say anything about profitability or parent company financial health (how many top 10 module suppliers have gone bankrupt over the years by accumulating excessive debt?); they don’t give an indication of parent company desire to retain manufacturing operations (think of Sharp, Kyocera, Bosch, BP, Panasonic and countless others in the past 20 years); and finally, they don’t inform as to the company’s ability to deliver quality products that work reliably in the field.

Rankings of module suppliers by specific financial metrics is also somewhat misleading, unless the context is clearly explained. Is the analysis purely for existing shareholders or short-sellers, or to inflate the enterprise value prior to selling off the business (as a whole or just the PV manufacturing part)? Some observers just pull out an Altman-Z score, while conveniently ignoring all the privately-held module suppliers in the industry at any given time. The Altman-Z score is of value, but not the way in which it is scantily used in the PV sector today in isolation.

The Altman-Z analysis is a statistically derived number based on adding a list of accounting ratios, each term having a weighted product factor. The final number (or score) used in isolation should be taken with great caution. What’s important is how the individual metrics (especially those related to liquidity, debt and profitability) are trending. As the analysis (in its original format) relates specifically to PV module suppliers (or parent entities today), market capitalisation is over-emphasised and turnover is under-prioritised. Put another way: some companies consistently have market caps way above any reasonable valuation; and module suppliers that are bankrolled by state-owned entities or US$100 billion-plus conglomerates tend to be pretty good bets in terms of parent entity guarantor when purchasing modules. It is unclear even if some of the stand-alone Altman-Z graphics used for PV module suppliers actually involve the people citing the numbers doing the financial analysis; anyone can pull a number off the internet.

Let’s look now at the PV ModuleTech Bankability Ratings pyramid at the start of 2022. For simplicity, think of it as you would with any credit ratings analysis. AAA-Rated is top, and C-Rated is the lowest. A pyramid-type representation works perfect for this, as there are always fewer companies at the top, and most others hover around the lower bands. Indeed, for the first time, we have split out sub-bands in the CCC and CC ratings, as most of the Top 50 fall into CCC or CC. This is shown below.

At the start of 2022, 50 module suppliers occupy bankability ratings of CC and above. Only six module suppliers have A-Grade ratings.

At the start of 2022, 50 module suppliers occupy bankability ratings of CC and above. Only six module suppliers have A-Grade ratings.

It just happens that there are exactly 50 suppliers rated CC or above; hence the use of ‘top 50’ for this article. These 50 companies make up more than 98% of global module supply today. To scupper any thoughts of ‘consolidation’, it should be remembered that there are more companies in the lowest rating band (C) than in all the ratings bands collectively above. Most of the (pure-play) OEMs fall into the ‘C’ band, in addition to ‘distributors’ that often like to call themselves module suppliers with GW-plus ‘capacity’. Making product should be king; more later on this subject.

Let’s review now what makes a company AAA-Rated, and what weighting should be applied to key manufacturing and financial metrics when doing any risk analysis (forward looking) as is undertaken every day by companies when short-listing suppliers as part of a due diligence process prior to a contract being awarded.

Manufacturing: strengths and weaknesses

Beyond anything else, consistently shipping multi-GW of modules annually to global utility-scale solar farms is key when it comes to manufacturing metrics feeding into the overall bankability ratings.

When we devised the methodology back in 2019, we decided to remove residential and small commercial shipment volumes from each module supplier’s shipment totals. Three years on, and I still consider this essential when it comes to bankability. If a company ships only to global residential markets (often through a network of low-volume sub-MW-scale distributors/installers), this makes the company’s ‘bankability’ for large utility-scale ground-mount projects negligible. Not having product availability – or simply deciding not to compete in large-scale utility business – is a major red flag in terms of being a bankable module supplier today for utility development. The PV industry is a 200GW engine today, fuelled by utility-scale projects; it is no longer a (European) residential FiT-driven sector.

Having a diversified global module supply footprint helps, but today it is not as essential as was previously the case. This is because there are now individual countries (or sales regions if you group, say Europe, together) that are so big that individual companies can supply multi-GW of product there alone each year. Also, solar PV now plays in a world that is smitten with renewables and awash with finance from the private sector. This de-risks legacy industry concerns relating to cyclic government policies or administrations, where market demand was based entirely on lucrative incentives or grants that could be taken away as quickly as introduced.

The only risk from the global supply model today comes from trade wars and import restrictions. However, this is more of a factor behind the next key manufacturing requirement – diversification in origin-of-manufacture.

Where a product is made is multi-faceted, and not simply about the ‘Made in’ label that appears on a module shipping carnet.

Firstly, it remains the case that the companies consistently at the top of the bankability ratings are the ones that make most of what they ship. Certainly cells and modules, but generally having control of in-house production from ingots to modules characterises industry leaders. The reasons for this are fairly obvious; controlling production costs, in-house quality control, the ability to manage each value chain stage when introducing new technologies/products, decoupling from supply chain bottlenecks and avoiding having to rely upon your module supply competitors that may be dominant suppliers of wafers or cells.

Secondly, having diversified manufacturing locations is vital to be in the very top ratings bands. This is the only way to mitigate against trade restrictions that may come and go at any given point. And linked to the above issue, making both cells and modules at overseas locations tends to be a key factor for long-term bankability success.

Finally, we have one of the most stealth-like (bordering on duplicitous) activities in the PV industry; re-branding product made by a different company and passing it off as your own product. Call me old-fashioned, but making your own product seems pretty logical to me, especially if these products are going to form the basis of 25-40 year financial models based on site yield.

Most c-Si module suppliers have dipped their toes in and out of OEM supply, some more than others. What started as a Japanese PV tactic ten years ago spread to Chinese companies when EU and US duties were imposed. Today we have Korean PV module suppliers having their products made in China or Southeast Asia and EU/US companies buying in modules made in China and Southeast Asia and rebranding them (acting more like distributors than manufacturers).

Surely, anyone buying OEM product (often from companies that are highly unlikely to exist in a few years) is taking a punt, or has no other choice to get product on time. Looking back over the bankability analysis, module suppliers that start to increase their reliance on OEM product usually have other problems waiting to surface. It tends to be one of the key leading indicators of pending non-competitiveness. And like their customers buying their module products, maybe at the end of the day, these module suppliers had no other choice if they wanted to play in any given market (e.g. in the US today).

Before we move to leading financial indicators, let’s consider two other manufacturing metrics: capex and R&D spending.

Capex is an incredibly important metric and is a key leading indicator for module supplier bankability. Companies that are constantly investing in capex – especially during any downturn – routinely end up in a good space in the future. Moreover, and linked to the above in-house value chain discussion, companies that invest each year across ingot, wafer, cell and module stages tend to be the minority in the industry. But these companies also are the ones driving the sector, from a module supply standpoint and also technology leadership. Conversely, companies that minimise capex are usually overly dependent on outsourcing and can be considered as laggards with regards to any technology adoption cycle. (A good reference point here is the article I wrote on PV Tech last week: Which PV manufacturers will really drive n-type industry adoption?)

R&D spending is an altogether different proposition, and one of the most misunderstood metrics in the PV industry; at least, until now. For starters, there is no consistency in how companies assign R&D spending when they report numbers in audited accounts. And while industry R&D spending has grown from US$1 billion to US$2 billion over the past few years, the numbers cannot be correlated with module supplier bankability ratings. It could be that R&D investment is being seen somewhat as a marketing-driven accolade, rather than an indication of true technology leadership. Maybe this will change in the future.

It turns out that a far better method of tracking R&D activity is looking at company-specific cell technology roadmap trends. Again, this highlights the importance of module suppliers that actually make their own solar cells (better still wafers and cells). This is much more important now than ever before in the industry, as technology is changing rapidly and more often. Basically, it is now possible to be left behind in technology very quickly.

Therefore, it is the combination of capex and cell technology roadmap for each PV module supplier that matters. Looking across the 100-plus companies supplying modules to the industry today, just four companies consistently meet the wafer-to-module capex and cell technology roadmap (or thin-film equivalent) criteria listed above; First Solar, JA Solar, JinkoSolar and LONGi Solar. It should come as no surprise then these companies are right at the top of the bankability pyramid shown above.

Financial: strengths and weaknesses

Benchmarking PV module suppliers by manufacturing metrics is easy: benchmarking across financial metrics or ratios is much harder. Not because numbers are hard to come by, but due to the differences in accounting methods used, market listing region (or if listed at all), and – most notably – how much PV module business matters to the holding/parent entity (or what I tend to refer to as module ‘guarantor’).

Before looking at typical leading indicators of pending supplier fortunes from a financial standpoint, it is interesting to look at the correlation between PV module supplier bankability status and how much of the parent entity’s turnover is coming from the module sales (whether external or internal sales). In fact, this is a fascinating metric to look at.

It turns out the most bankable (least risk of being around, say, in 5-10 years) module suppliers have been operating in a sweet spot where module revenue contributions are not extremely high (more than 95% of turnover) or extremely low (less than 5% of turnover). The best case appears to be when module revenues contribute about 60-80% of parent company turnover. This is relatively easy to explain.

Where module revenues are the only form of income then effectively you can have a billion-dollar-plus company selling one product. For any business in any sector – anywhere in the world – that is a risky proposition. Great in good times; potentially disastrous when confronted by any unforeseen issue (company-specific or industry-wide), unless there is tons of money in the bank. Basically, there is no other revenue stream for these companies to fall back on, if module sales are not profitable. Time and again, the PV industry has seen leading module suppliers go from hero to zero essentially because there was no ‘plan B’ in place. While no one can predict the future, the only certainty is that there will be uncertainty at some point.

The other extreme turns out to be just as risky; where the module business is so small it doesn’t really matter (and by default can operate with whopping losses so long as the parent company can write these off at some point). Probably the most striking example of this was seen in Japan, and the time it took companies such as Sharp, Kyocera and Panasonic to recognise that being a PV module supplier was a tough proposition.

You really don’t want to be a module supplier where module sales are lost in the noise compared to your parent company’s turnover. Almost certainly, at some point, PV manufacturing is stopped and recognised to be a distraction.

Korea has gone down a slightly different route here than Japan, although it was looking for a while like Korean PV module supply had ‘Japan’ written all over it but with a 5-10 year phase lag. Hyundai and Hanwha decided to establish separately listed (albeit still held) entities, within which module sales had an appreciable contribution. It is impossible to tell today if LG will move in this direction. For each of the Korean entities, it is a fairly easy way of writing off consolidated debt from legacy PV manufacturing and re-start a listed spin-out with apparently healthy-looking financial credentials. Time will tell if this turns out a smart move.

The sweet spot is where module sales are the most important part of the business, but not all of the business. It has to be the most important part, or else investment (capex) and technology does not get prioritised.

Until now, there is really not a PV module supplier that has got this right long-term. LONGi has wafer sales, but this is still PV and would collapse under similar conditions that could harm module sales. First Solar has drifted in and out of downstream activities, but is now at risk of having one product almost entirely sold in one country. Canadian Solar’s diversification into project development (flipping post build) actually became so successful that the module business suffered in the past few years, and ultimately the spin-out into the China-listed CSI Solar was more for the benefit of the reshaped US-listed Canadian Solar (projects) than for the new manufacturing entity in China (CSI Solar).

In fact, it is very hard to operate a profitable PV module business (making and selling products in a factory) alongside a PV projects business (project planning, investment, trading energy). The skill sets are somewhat mutually exclusive. Just because you can make a PV module does not qualify you to develop, build and operate sites. This is exactly the trap Canadian Solar ended up in, and also was behind other spectacular declines of module supply activities within the holding entities of Shunfeng and GCL, for example.

I actually think that the ideal PV module supplier is yet to exist in this regard. Maybe it will in the next few years, say from having two to three different revenues streams (such as PV modules, storage batteries, and something else). Each would benefit from the core strength of volume manufacturing, alongside a diversified global sales model; business units could stand alone, but also have some kind of synergy in manufacturing and selling. Interestingly, this does seem to be the Hanwha/Hyundai approach with their new spin-out operations; but it’s hard though to see either being a top three global player though when it comes to PV module sales (far less a top 10 player in the long run).

So – what else matters from a financial health perspective, in terms of module supplier risk? This is not rocket science: keep clear of liquidity problems (cash flow), don’t accumulate long-term debt faster than accumulating assets, and make money selling modules. The most common red flag for PV module suppliers is cash flow. Again, if you have one product (making/selling modules), and you know routinely that there will be periods where costs and higher than income from selling this one product, then of course, working capital is going to take a hit routinely. It is amazing how often this is the first sign of bigger problems with PV module suppliers, and it is not a surprise at all.

Learning more about PV module suppliers’ bankability status

I wrote this article now, as the next few weeks sees our in-house market research team at PV Tech flat-out in preparation for the next quarterly release of our flagship PV ModuleTech Bankability Ratings Quarterly report on 1 March 2022.

Three years into the report, and it is fascinating how much has been learned by doing all the analysis across basically every PV module supplier that matters. The benchmarking is constantly evolving, and we are now doing calendar-year-end forecasting (all manufacturing and financial metrics) for all module suppliers; so, right now through to the end of Q4’22.

The entire report is now written as if we were indeed buying or financing 300MW worth of PV modules for 2023 delivery, and our livelihoods depended on it. This seems to be where all our report users are today!